Golden ratio

| |

| Representations | |

|---|---|

| Decimal | 1.618033988749894 . . . [1] |

| Algebraic form | |

| Continued fraction | |

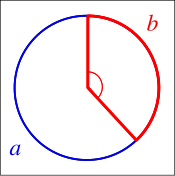

In mathematics, two quantities are in the golden ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities. Expressed algebraically, for quantities and with , is in a golden ratio to if

where the Greek letter phi ( or ) denotes the golden ratio.[a] The constant satisfies the quadratic equation and is an irrational number with a value of[1]

The golden ratio was called the extreme and mean ratio by Euclid,[2] and the divine proportion by Luca Pacioli;[3] it also goes by other names.[b]

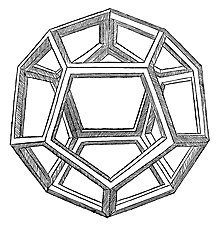

Mathematicians have studied the golden ratio's properties since antiquity. It is the ratio of a regular pentagon's diagonal to its side and thus appears in the construction of the dodecahedron and icosahedron.[7] A golden rectangle—that is, a rectangle with an aspect ratio of —may be cut into a square and a smaller rectangle with the same aspect ratio. The golden ratio has been used to analyze the proportions of natural objects and artificial systems such as financial markets, in some cases based on dubious fits to data.[8] The golden ratio appears in some patterns in nature, including the spiral arrangement of leaves and other parts of vegetation.

Some 20th-century artists and architects, including Le Corbusier and Salvador Dalí, have proportioned their works to approximate the golden ratio, believing it to be aesthetically pleasing. These uses often appear in the form of a golden rectangle.

Calculation

Two quantities and are in the golden ratio if[9]

Thus, if we want to find , we may use that the definition above holds for arbitrary ; thus, we just set , in which case and we get the equation , which becomes a quadratic equation after multiplying by : which can be rearranged to

The quadratic formula yields two solutions:

Because is a ratio between positive quantities, is necessarily the positive root.[10] The negative root is in fact the negative inverse , which shares many properties with the golden ratio.

History

According to Mario Livio,

Some of the greatest mathematical minds of all ages, from Pythagoras and Euclid in ancient Greece, through the medieval Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa and the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, to present-day scientific figures such as Oxford physicist Roger Penrose, have spent endless hours over this simple ratio and its properties. ... Biologists, artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and even mystics have pondered and debated the basis of its ubiquity and appeal. In fact, it is probably fair to say that the Golden Ratio has inspired thinkers of all disciplines like no other number in the history of mathematics.[11]

— The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number

Ancient Greek mathematicians first studied the golden ratio because of its frequent appearance in geometry;[12] the division of a line into "extreme and mean ratio" (the golden section) is important in the geometry of regular pentagrams and pentagons.[13] According to one story, 5th-century BC mathematician Hippasus discovered that the golden ratio was neither a whole number nor a fraction (it is irrational), surprising Pythagoreans.[14] Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BC) provides several propositions and their proofs employing the golden ratio,[15][c] and contains its first known definition which proceeds as follows:[16]

A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the lesser.[17][d]

The golden ratio was studied peripherally over the next millennium. Abu Kamil (c. 850–930) employed it in his geometric calculations of pentagons and decagons; his writings influenced that of Fibonacci (Leonardo of Pisa) (c. 1170–1250), who used the ratio in related geometry problems but did not observe that it was connected to the Fibonacci numbers.[19]

Luca Pacioli named his book Divina proportione (1509) after the ratio; the book, largely plagiarized from Piero della Francesca, explored its properties including its appearance in some of the Platonic solids.[20][21] Leonardo da Vinci, who illustrated Pacioli's book, called the ratio the sectio aurea ('golden section').[22] Though it is often said that Pacioli advocated the golden ratio's application to yield pleasing, harmonious proportions, Livio points out that the interpretation has been traced to an error in 1799, and that Pacioli actually advocated the Vitruvian system of rational proportions.[23] Pacioli also saw Catholic religious significance in the ratio, which led to his work's title. 16th-century mathematicians such as Rafael Bombelli solved geometric problems using the ratio.[24]

German mathematician Simon Jacob (d. 1564) noted that consecutive Fibonacci numbers converge to the golden ratio;[25] this was rediscovered by Johannes Kepler in 1608.[26] The first known decimal approximation of the (inverse) golden ratio was stated as "about " in 1597 by Michael Maestlin of the University of Tübingen in a letter to Kepler, his former student.[27] The same year, Kepler wrote to Maestlin of the Kepler triangle, which combines the golden ratio with the Pythagorean theorem. Kepler said of these:

Geometry has two great treasures: one is the theorem of Pythagoras, the other the division of a line into extreme and mean ratio. The first we may compare to a mass of gold, the second we may call a precious jewel.[28]

Eighteenth-century mathematicians Abraham de Moivre, Nicolaus I Bernoulli, and Leonhard Euler used a golden ratio-based formula which finds the value of a Fibonacci number based on its placement in the sequence; in 1843, this was rediscovered by Jacques Philippe Marie Binet, for whom it was named "Binet's formula".[29] Martin Ohm first used the German term goldener Schnitt ('golden section') to describe the ratio in 1835.[30] James Sully used the equivalent English term in 1875.[31]

By 1910, inventor Mark Barr began using the Greek letter phi () as a symbol for the golden ratio.[32][e] It has also been represented by tau (), the first letter of the ancient Greek τομή ('cut' or 'section').[35]

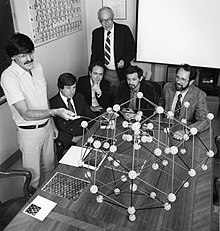

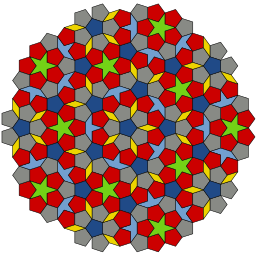

The zome construction system, developed by Steve Baer in the late 1960s, is based on the symmetry system of the icosahedron/dodecahedron, and uses the golden ratio ubiquitously. Between 1973 and 1974, Roger Penrose developed Penrose tiling, a pattern related to the golden ratio both in the ratio of areas of its two rhombic tiles and in their relative frequency within the pattern.[36] This gained in interest after Dan Shechtman's Nobel-winning 1982 discovery of quasicrystals with icosahedral symmetry, which were soon afterwards explained through analogies to the Penrose tiling.[37]

Mathematics

Irrationality

The golden ratio is an irrational number. Below are two short proofs of irrationality:

Contradiction from an expression in lowest terms

This is a proof by infinite descent. Recall that:

the whole is to the longer part as the longer part is to the shorter part.

If we call the whole and the longer part , then the second statement above becomes

To say that the golden ratio is rational means that is a fraction where and are integers. We may take to be in lowest terms and and to be positive. But if is in lowest terms, then the equally valued is in still lower terms. That is a contradiction that follows from the assumption that is rational.

By irrationality of the square root of 5

Another short proof – perhaps more commonly known – of the irrationality of the golden ratio makes use of the closure of rational numbers under addition and multiplication. If is assumed to be rational, then , the square root of , must also be rational. This is a contradiction as the square roots of all non-square natural numbers are irrational.[f]

Minimal polynomial

The golden ratio is also an algebraic number and even an algebraic integer. It has minimal polynomial

This quadratic polynomial has two roots, and .

The golden ratio is also closely related to the polynomial , which has roots and . As the root of a quadratic polynomial, the golden ratio is a constructible number.[38]

Golden ratio conjugate and powers

The conjugate root to the minimal polynomial is

The absolute value of this quantity () corresponds to the length ratio taken in reverse order (shorter segment length over longer segment length, ).

This illustrates the unique property of the golden ratio among positive numbers, that

or its inverse,

The conjugate and the defining quadratic polynomial relationship lead to decimal values that have their fractional part in common with :

The sequence of powers of contains these values , , , ; more generally, any power of is equal to the sum of the two immediately preceding powers:

As a result, one can easily decompose any power of into a multiple of and a constant. The multiple and the constant are always adjacent Fibonacci numbers. This leads to another property of the positive powers of :

If , then:

Continued fraction and square root

The formula can be expanded recursively to obtain a simple continued fraction for the golden ratio:[39]

It is in fact the simplest form of a continued fraction, alongside its reciprocal form:

The convergents of these continued fractions, , , , , , , ... or , , , , , , ..., are ratios of successive Fibonacci numbers. The consistently small terms in its continued fraction explain why the approximants converge so slowly. This makes the golden ratio an extreme case of the Hurwitz inequality for Diophantine approximations, which states that for every irrational , there are infinitely many distinct fractions such that,

This means that the constant cannot be improved without excluding the golden ratio. It is, in fact, the smallest number that must be excluded to generate closer approximations of such Lagrange numbers.[40]

A continued square root form for can be obtained from , yielding:[41]

Relationship to Fibonacci and Lucas numbers

Fibonacci numbers and Lucas numbers have an intricate relationship with the golden ratio. In the Fibonacci sequence, each term is equal to the sum of the preceding two terms and , starting with the base sequence as the 0th and 1st terms and :

The sequence of Lucas numbers (not to be confused with the generalized Lucas sequences, of which this is part) is like the Fibonacci sequence, in that each term is the sum of the previous two terms and , however instead starts with as the 0th and 1st terms and :

Exceptionally, the golden ratio is equal to the limit of the ratios of successive terms in the Fibonacci sequence and sequence of Lucas numbers:[42]

In other words, if a Fibonacci and Lucas number is divided by its immediate predecessor in the sequence, the quotient approximates . For example,

These approximations are alternately lower and higher than , and converge to as the Fibonacci and Lucas numbers increase.

Closed-form expressions for the Fibonacci and Lucas sequences that involve the golden ratio are:

Combining both formulas above, one obtains a formula for that involves both Fibonacci and Lucas numbers:

Between Fibonacci and Lucas numbers one can deduce , which simplifies to express the limit of the quotient of Lucas numbers by Fibonacci numbers as equal to the square root of five:

Indeed, much stronger statements are true:

These values describe as a fundamental unit of the algebraic number field .

Successive powers of the golden ratio obey the Fibonacci recurrence, .

The reduction to a linear expression can be accomplished in one step by using:

This identity allows any polynomial in to be reduced to a linear expression, as in:

Consecutive Fibonacci numbers can also be used to obtain a similar formula for the golden ratio, here by infinite summation:

In particular, the powers of themselves round to Lucas numbers (in order, except for the first two powers, and , are in reverse order):

and so forth.[43] The Lucas numbers also directly generate powers of the golden ratio; for :

Rooted in their interconnecting relationship with the golden ratio is the notion that the sum of third consecutive Fibonacci numbers equals a Lucas number, that is ; and, importantly, that .

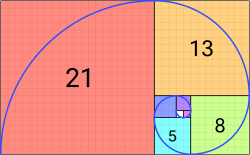

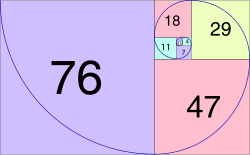

Both the Fibonacci sequence and the sequence of Lucas numbers can be used to generate approximate forms of the golden spiral (which is a special form of a logarithmic spiral) using quarter-circles with radii from these sequences, differing only slightly from the true golden logarithmic spiral. Fibonacci spiral is generally the term used for spirals that approximate golden spirals using Fibonacci number-sequenced squares and quarter-circles.

Geometry

The golden ratio features prominently in geometry. For example, it is intrinsically involved in the internal symmetry of the pentagon, and extends to form part of the coordinates of the vertices of a regular dodecahedron, as well as those of a regular icosahedron.[44] It features in the Kepler triangle and Penrose tilings too, as well as in various other polytopes.

Construction

Dividing by interior division

- Having a line segment , construct a perpendicular at point , with half the length of . Draw the hypotenuse .

- Draw an arc with center and radius . This arc intersects the hypotenuse at point .

- Draw an arc with center and radius . This arc intersects the original line segment at point . Point divides the original line segment into line segments and with lengths in the golden ratio.

Dividing by exterior division

- Draw a line segment and construct off the point a segment perpendicular to and with the same length as .

- Do bisect the line segment with .

- A circular arc around with radius intersects in point the straight line through points and (also known as the extension of ). The ratio of to the constructed segment is the golden ratio.

Application examples you can see in the articles Pentagon with a given side length, Decagon with given circumcircle and Decagon with a given side length.

Both of the above displayed different algorithms produce geometric constructions that determine two aligned line segments where the ratio of the longer one to the shorter one is the golden ratio.

Golden angle

When two angles that make a full circle have measures in the golden ratio, the smaller is called the golden angle, with measure :

This angle occurs in patterns of plant growth as the optimal spacing of leaf shoots around plant stems so that successive leaves do not block sunlight from the leaves below them.[45]

Pentagonal symmetry system

Pentagon and pentagram

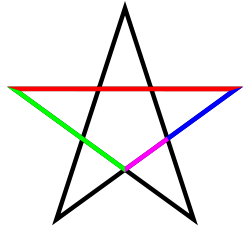

In a regular pentagon the ratio of a diagonal to a side is the golden ratio, while intersecting diagonals section each other in the golden ratio. The golden ratio properties of a regular pentagon can be confirmed by applying Ptolemy's theorem to the quadrilateral formed by removing one of its vertices. If the quadrilateral's long edge and diagonals are , and short edges are , then Ptolemy's theorem gives . Dividing both sides by yields (see § Calculation above),

The diagonal segments of a pentagon form a pentagram, or five-pointed star polygon, whose geometry is quintessentially described by . Primarily, each intersection of edges sections other edges in the golden ratio. The ratio of the length of the shorter segment to the segment bounded by the two intersecting edges (that is, a side of the inverted pentagon in the pentagram's center) is , as the four-color illustration shows.

Pentagonal and pentagrammic geometry permits us to calculate the following values for :

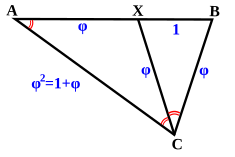

Golden triangle and golden gnomon

The triangle formed by two diagonals and a side of a regular pentagon is called a golden triangle or sublime triangle. It is an acute isosceles triangle with apex angle and base angles .[46] Its two equal sides are in the golden ratio to its base.[47] The triangle formed by two sides and a diagonal of a regular pentagon is called a golden gnomon. It is an obtuse isosceles triangle with apex angle and base angle . Its base is in the golden ratio to its two equal sides.[47] The pentagon can thus be subdivided into two golden gnomons and a central golden triangle. The five points of a regular pentagram are golden triangles,[47] as are the ten triangles formed by connecting the vertices of a regular decagon to its center point.[48]

Bisecting one of the base angles of the golden triangle subdivides it into a smaller golden triangle and a golden gnomon. Analogously, any acute isosceles triangle can be subdivided into a similar triangle and an obtuse isosceles triangle, but the golden triangle is the only one for which this subdivision is made by the angle bisector, because it is the only isosceles triangle whose base angle is twice its apex angle. The angle bisector of the golden triangle subdivides the side that it meets in the golden ratio, and the areas of the two subdivided pieces are also in the golden ratio.[47]

If the apex angle of the golden gnomon is trisected, the trisector again subdivides it into a smaller golden gnomon and a golden triangle. The trisector subdivides the base in the golden ratio, and the two pieces have areas in the golden ratio. Analogously, any obtuse triangle can be subdivided into a similar triangle and an acute isosceles triangle, but the golden gnomon is the only one for which this subdivision is made by the angle trisector, because it is the only isosceles triangle whose apex angle is three times its base angle.[47]

Penrose tilings

The golden ratio appears prominently in the Penrose tiling, a family of aperiodic tilings of the plane developed by Roger Penrose, inspired by Johannes Kepler's remark that pentagrams, decagons, and other shapes could fill gaps that pentagonal shapes alone leave when tiled together.[49] Several variations of this tiling have been studied, all of whose prototiles exhibit the golden ratio:

- Penrose's original version of this tiling used four shapes: regular pentagons and pentagrams, "boat" figures with three points of a pentagram, and "diamond" shaped rhombi.[50]

- The kite and dart Penrose tiling uses kites with three interior angles of and one interior angle of , and darts, concave quadrilaterals with two interior angles of , one of , and one non-convex angle of . Special matching rules restrict how the tiles can meet at any edge, resulting in seven combinations of tiles at any vertex. Both the kites and darts have sides of two lengths, in the golden ratio to each other. The areas of these two tile shapes are also in the golden ratio to each other.[49]

- The kite and dart can each be cut on their symmetry axes into a pair of golden triangles and golden gnomons, respectively. With suitable matching rules, these triangles, called in this context Robinson triangles, can be used as the prototiles for a form of the Penrose tiling.[49][51]

- The rhombic Penrose tiling contains two types of rhombus, a thin rhombus with angles of and , and a thick rhombus with angles of and . All side lengths are equal, but the ratio of the length of sides to the short diagonal in the thin rhombus equals , as does the ratio of the sides of to the long diagonal of the thick rhombus. As with the kite and dart tiling, the areas of the two rhombi are in the golden ratio to each other. Again, these rhombi can be decomposed into pairs of Robinson triangles.[49]

In triangles and quadrilaterals

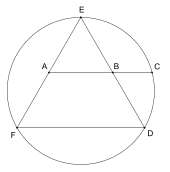

Odom's construction

George Odom found a construction for involving an equilateral triangle: if the line segment joining the midpoints of two sides is extended to intersect the circumcircle, then the two midpoints and the point of intersection with the circle are in golden proportion.[52]

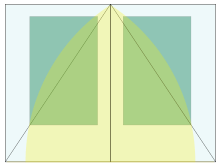

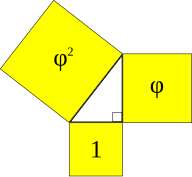

Kepler triangle

The Kepler triangle, named after Johannes Kepler, is the unique right triangle with sides in geometric progression: These side lengths are the three Pythagorean means of the two numbers . The three squares on its sides have areas in the golden geometric progression .

Among isosceles triangles, the ratio of inradius to side length is maximized for the triangle formed by two reflected copies of the Kepler triangle, sharing the longer of their two legs.[53] The same isosceles triangle maximizes the ratio of the radius of a semicircle on its base to its perimeter.[54]

For a Kepler triangle with smallest side length , the area and acute internal angles are:

Golden rectangle

| Draw a square. |

| Draw a line from the midpoint of one side of the square to an opposite corner. |

| Use that line as the radius to draw an arc that defines the height of the rectangle. |

| Complete the golden rectangle. |

The golden ratio proportions the adjacent side lengths of a golden rectangle in ratio.[55] Stacking golden rectangles produces golden rectangles anew, and removing or adding squares from golden rectangles leaves rectangles still proportioned in ratio. They can be generated by golden spirals, through successive Fibonacci and Lucas number-sized squares and quarter circles. They feature prominently in the icosahedron as well as in the dodecahedron (see section below for more detail).[44]

Golden rhombus

A golden rhombus is a rhombus whose diagonals are in proportion to the golden ratio, most commonly .[56] For a rhombus of such proportions, its acute angle and obtuse angles are:

The lengths of its short and long diagonals and , in terms of side length are:

Its area, in terms of and :

Its inradius, in terms of side :

Golden rhombi form the faces of the rhombic triacontahedron, the two golden rhombohedra, the Bilinski dodecahedron,[57] and the rhombic hexecontahedron.[56]

Golden spiral

Logarithmic spirals are self-similar spirals where distances covered per turn are in geometric progression. A logarithmic spiral whose radius increases by a factor of the golden ratio for each quarter-turn is called the golden spiral. These spirals can be approximated by quarter-circles that grow by the golden ratio,[59] or their approximations generated from Fibonacci numbers,[60] often depicted inscribed within a spiraling pattern of squares growing in the same ratio. The exact logarithmic spiral form of the golden spiral can be described by the polar equation with :

Not all logarithmic spirals are connected to the golden ratio, and not all spirals that are connected to the golden ratio are the same shape as the golden spiral. For instance, a different logarithmic spiral, encasing a nested sequence of golden isosceles triangles, grows by the golden ratio for each that it turns, instead of the turning angle of the golden spiral.[58] Another variation, called the "better golden spiral", grows by the golden ratio for each half-turn, rather than each quarter-turn.[59]

Dodecahedron and icosahedron

| Cartesian coordinates of the dodecahedron : | ||

| (±1, ±1, ±1) | ||

| (0, ±φ, ±1/φ) | ||

| (±1/φ, 0, ±φ) | ||

| (±φ, ±1/φ, 0) | ||

| A nested cube inside the dodecahedron is represented with dotted lines. | ||

The regular dodecahedron and its dual polyhedron the icosahedron are Platonic solids whose dimensions are related to the golden ratio. A dodecahedron has regular pentagonal faces, whereas an icosahedron has equilateral triangles; both have edges.[61]

For a dodecahedron of side , the radius of a circumscribed and inscribed sphere, and midradius are (, , and , respectively):

While for an icosahedron of side , the radius of a circumscribed and inscribed sphere, and midradius are:

The volume and surface area of the dodecahedron can be expressed in terms of :

As well as for the icosahedron:

These geometric values can be calculated from their Cartesian coordinates, which also can be given using formulas involving . The coordinates of the dodecahedron are displayed on the figure to the right, while those of the icosahedron are:

Sets of three golden rectangles intersect perpendicularly inside dodecahedra and icosahedra, forming Borromean rings.[62][44] In dodecahedra, pairs of opposing vertices in golden rectangles meet the centers of pentagonal faces, and in icosahedra, they meet at its vertices. The three golden rectangles together contain all vertices of the icosahedron, or equivalently, intersect the centers of all of the dodecahedron's faces.[61]

A cube can be inscribed in a regular dodecahedron, with some of the diagonals of the pentagonal faces of the dodecahedron serving as the cube's edges; therefore, the edge lengths are in the golden ratio. The cube's volume is times that of the dodecahedron's.[63] In fact, golden rectangles inside a dodecahedron are in golden proportions to an inscribed cube, such that edges of a cube and the long edges of a golden rectangle are themselves in ratio. On the other hand, the octahedron, which is the dual polyhedron of the cube, can inscribe an icosahedron, such that an icosahedron's vertices touch the edges of an octahedron at points that divide its edges in golden ratio.[64]

Other properties

The golden ratio's decimal expansion can be calculated via root-finding methods, such as Newton's method or Halley's method, on the equation or on (to compute first). The time needed to compute digits of the golden ratio using Newton's method is essentially , where is the time complexity of multiplying two -digit numbers.[65] This is considerably faster than known algorithms for π and e. An easily programmed alternative using only integer arithmetic is to calculate two large consecutive Fibonacci numbers and divide them. The ratio of Fibonacci numbers and , each over digits, yields over significant digits of the golden ratio. The decimal expansion of the golden ratio [1] has been calculated to an accuracy of twenty trillion () digits.[66]

In the complex plane, the fifth roots of unity (for an integer ) satisfying are the vertices of a pentagon. They do not form a ring of quadratic integers, however the sum of any fifth root of unity and its complex conjugate, , is a quadratic integer, an element of . Specifically,

This also holds for the remaining tenth roots of unity satisfying ,

For the gamma function , the only solutions to the equation are and .

When the golden ratio is used as the base of a numeral system (see golden ratio base, sometimes dubbed phinary or -nary), quadratic integers in the ring – that is, numbers of the form for and in – have terminating representations, but rational fractions have non-terminating representations.

The golden ratio also appears in hyperbolic geometry, as the maximum distance from a point on one side of an ideal triangle to the closer of the other two sides: this distance, the side length of the equilateral triangle formed by the points of tangency of a circle inscribed within the ideal triangle, is .[67]

The golden ratio appears in the theory of modular functions as well. For let Then and where and in the continued fraction should be evaluated as . The function is invariant under , a congruence subgroup of the modular group. Also for positive real numbers and such that [68]

is a Pisot–Vijayaraghavan number.[69]

Applications and observations

Architecture

The Swiss architect Le Corbusier, famous for his contributions to the modern international style, centered his design philosophy on systems of harmony and proportion. Le Corbusier's faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden ratio and the Fibonacci series, which he described as "rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section by children, old men, savages and the learned."[70][71]

Le Corbusier explicitly used the golden ratio in his Modulor system for the scale of architectural proportion. He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man", the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture.

In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit. He took suggestion of the golden ratio in human proportions to an extreme: he sectioned his model human body's height at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then subdivided those sections in golden ratio at the knees and throat; he used these golden ratio proportions in the Modulor system. Le Corbusier's 1927 Villa Stein in Garches exemplified the Modulor system's application. The villa's rectangular ground plan, elevation, and inner structure closely approximate golden rectangles.[72]

Another Swiss architect, Mario Botta, bases many of his designs on geometric figures. Several private houses he designed in Switzerland are composed of squares and circles, cubes and cylinders. In a house he designed in Origlio, the golden ratio is the proportion between the central section and the side sections of the house.[73]

Art

Leonardo da Vinci's illustrations of polyhedra in Pacioli's Divina proportione have led some to speculate that he incorporated the golden ratio in his paintings. But the suggestion that his Mona Lisa, for example, employs golden ratio proportions, is not supported by Leonardo's own writings.[74] Similarly, although Leonardo's Vitruvian Man is often shown in connection with the golden ratio, the proportions of the figure do not actually match it, and the text only mentions whole number ratios.[75][76]

Salvador Dalí, influenced by the works of Matila Ghyka,[77] explicitly used the golden ratio in his masterpiece, The Sacrament of the Last Supper. The dimensions of the canvas are a golden rectangle. A huge dodecahedron, in perspective so that edges appear in golden ratio to one another, is suspended above and behind Jesus and dominates the composition.[74][78]

A statistical study on 565 works of art of different great painters, performed in 1999, found that these artists had not used the golden ratio in the size of their canvases. The study concluded that the average ratio of the two sides of the paintings studied is , with averages for individual artists ranging from (Goya) to (Bellini).[79] On the other hand, Pablo Tosto listed over 350 works by well-known artists, including more than 100 which have canvasses with golden rectangle and proportions, and others with proportions like , , , and .[80]

Books and design

According to Jan Tschichold,

There was a time when deviations from the truly beautiful page proportions , , and the Golden Section were rare. Many books produced between 1550 and 1770 show these proportions exactly, to within half a millimeter.[82]

According to some sources, the golden ratio is used in everyday design, for example in the proportions of playing cards, postcards, posters, light switch plates, and widescreen televisions.[83]

Flags

The aspect ratio (width to height ratio) of the flag of Togo was intended to be the golden ratio, according to its designer.[84]

Music

Ernő Lendvai analyzes Béla Bartók's works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden ratio and the acoustic scale,[85] though other music scholars reject that analysis.[86] French composer Erik Satie used the golden ratio in several of his pieces, including Sonneries de la Rose+Croix. The golden ratio is also apparent in the organization of the sections in the music of Debussy's Reflets dans l'eau (Reflections in water), from Images (1st series, 1905), in which "the sequence of keys is marked out by the intervals 34, 21, 13 and 8, and the main climax sits at the phi position".[87]

The musicologist Roy Howat has observed that the formal boundaries of Debussy's La Mer correspond exactly to the golden section.[88] Trezise finds the intrinsic evidence "remarkable", but cautions that no written or reported evidence suggests that Debussy consciously sought such proportions.[89]

Music theorists including Hans Zender and Heinz Bohlen have experimented with the 833 cents scale, a musical scale based on using the golden ratio as its fundamental musical interval. When measured in cents, a logarithmic scale for musical intervals, the golden ratio is approximately 833.09 cents.[90]

Nature

Johannes Kepler wrote that "the image of man and woman stems from the divine proportion. In my opinion, the propagation of plants and the progenitive acts of animals are in the same ratio".[91]

The psychologist Adolf Zeising noted that the golden ratio appeared in phyllotaxis and argued from these patterns in nature that the golden ratio was a universal law.[92] Zeising wrote in 1854 of a universal orthogenetic law of "striving for beauty and completeness in the realms of both nature and art".[93]

However, some have argued that many apparent manifestations of the golden ratio in nature, especially in regard to animal dimensions, are fictitious.[94]

Physics

The quasi-one-dimensional Ising ferromagnet (cobalt niobate) has predicted excitation states (with symmetry), that when probed with neutron scattering, showed its lowest two were in golden ratio. Specifically, these quantum phase transitions during spin excitation, which occur at near absolute zero temperature, showed pairs of kinks in its ordered-phase to spin-flips in its paramagnetic phase; revealing, just below its critical field, a spin dynamics with sharp modes at low energies approaching the golden mean.[95]

Optimization

There is no known general algorithm to arrange a given number of nodes evenly on a sphere, for any of several definitions of even distribution (see, for example, Thomson problem or Tammes problem). However, a useful approximation results from dividing the sphere into parallel bands of equal surface area and placing one node in each band at longitudes spaced by a golden section of the circle, i.e. . This method was used to arrange the mirrors of the student-participatory satellite Starshine-3.[96]

The golden ratio is a critical element to golden-section search as well.

Disputed observations

Examples of disputed observations of the golden ratio include the following:

- Specific proportions in the bodies of vertebrates (including humans) are often claimed to be in the golden ratio; for example the ratio of successive phalangeal and metacarpal bones (finger bones) has been said to approximate the golden ratio. There is a large variation in the real measures of these elements in specific individuals, however, and the proportion in question is often significantly different from the golden ratio.[97][98]

- The shells of mollusks such as the nautilus are often claimed to be in the golden ratio.[99] The growth of nautilus shells follows a logarithmic spiral, and it is sometimes erroneously claimed that any logarithmic spiral is related to the golden ratio,[100] or sometimes claimed that each new chamber is golden-proportioned relative to the previous one.[101] However, measurements of nautilus shells do not support this claim.[102]

- Historian John Man states that both the pages and text area of the Gutenberg Bible were "based on the golden section shape". However, according to his own measurements, the ratio of height to width of the pages is .[103]

- Studies by psychologists, starting with Gustav Fechner c. 1876,[104] have been devised to test the idea that the golden ratio plays a role in human perception of beauty. While Fechner found a preference for rectangle ratios centered on the golden ratio, later attempts to carefully test such a hypothesis have been, at best, inconclusive.[105][74]

- In investing, some practitioners of technical analysis use the golden ratio to indicate support of a price level, or resistance to price increases, of a stock or commodity; after significant price changes up or down, new support and resistance levels are supposedly found at or near prices related to the starting price via the golden ratio.[106] The use of the golden ratio in investing is also related to more complicated patterns described by Fibonacci numbers (e.g. Elliott wave principle and Fibonacci retracement). However, other market analysts have published analyses suggesting that these percentages and patterns are not supported by the data.[107]

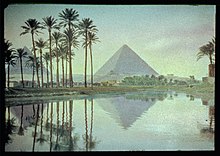

Egyptian pyramids

The Great Pyramid of Giza (also known as the Pyramid of Cheops or Khufu) has been analyzed by pyramidologists as having a doubled Kepler triangle as its cross-section. If this theory were true, the golden ratio would describe the ratio of distances from the midpoint of one of the sides of the pyramid to its apex, and from the same midpoint to the center of the pyramid's base. However, imprecision in measurement caused in part by the removal of the outer surface of the pyramid makes it impossible to distinguish this theory from other numerical theories of the proportions of the pyramid, based on pi or on whole-number ratios. The consensus of modern scholars is that this pyramid's proportions are not based on the golden ratio, because such a basis would be inconsistent both with what is known about Egyptian mathematics from the time of construction of the pyramid, and with Egyptian theories of architecture and proportion used in their other works.[108]

The Parthenon

The Parthenon's façade (c. 432 BC) as well as elements of its façade and elsewhere are said by some to be circumscribed by golden rectangles.[110] Other scholars deny that the Greeks had any aesthetic association with golden ratio. For example, Keith Devlin says, "Certainly, the oft repeated assertion that the Parthenon in Athens is based on the golden ratio is not supported by actual measurements. In fact, the entire story about the Greeks and golden ratio seems to be without foundation."[111] Midhat J. Gazalé affirms that "It was not until Euclid ... that the golden ratio's mathematical properties were studied."[112]

From measurements of 15 temples, 18 monumental tombs, 8 sarcophagi, and 58 grave stelae from the fifth century BC to the second century AD, one researcher concluded that the golden ratio was totally absent from Greek architecture of the classical fifth century BC, and almost absent during the following six centuries.[113] Later sources like Vitruvius (first century BC) exclusively discuss proportions that can be expressed in whole numbers, i.e. commensurate as opposed to irrational proportions.

Modern art

The Section d'Or ('Golden Section') was a collective of painters, sculptors, poets and critics associated with Cubism and Orphism.[114] Active from 1911 to around 1914, they adopted the name both to highlight that Cubism represented the continuation of a grand tradition, rather than being an isolated movement, and in homage to the mathematical harmony associated with Georges Seurat.[115] (Several authors have claimed that Seurat employed the golden ratio in his paintings, but Seurat's writings and paintings suggest that he employed simple whole-number ratios and any approximation of the golden ratio was coincidental.)[116] The Cubists observed in its harmonies, geometric structuring of motion and form, "the primacy of idea over nature", "an absolute scientific clarity of conception".[117] However, despite this general interest in mathematical harmony, whether the paintings featured in the celebrated 1912 Salon de la Section d'Or exhibition used the golden ratio in any compositions is more difficult to determine. Livio, for example, claims that they did not,[118] and Marcel Duchamp said as much in an interview.[119] On the other hand, an analysis suggests that Juan Gris made use of the golden ratio in composing works that were likely, but not definitively, shown at the exhibition.[119][120] Art historian Daniel Robbins has argued that in addition to referencing the mathematical term, the exhibition's name also refers to the earlier Bandeaux d'Or group, with which Albert Gleizes and other former members of the Abbaye de Créteil had been involved.[121]

Piet Mondrian has been said to have used the golden section extensively in his geometrical paintings,[122] though other experts (including critic Yve-Alain Bois) have discredited these claims.[74][123]

See also

- List of works designed with the golden ratio

- Metallic mean

- Plastic ratio

- Sacred geometry

- Supergolden ratio

- Silver ratio

References

Explanatory footnotes

- ^ If the constraint on and each being greater than zero is lifted, then there are actually two solutions, one positive and one negative, to this equation. is defined as the positive solution. The negative solution is . The sum of the two solutions is , and the product of the two solutions is .

- ^ Other names include the golden mean, golden section,[4] golden cut,[5] golden proportion, golden number,[6] medial section, and divine section.

- ^ Euclid, Elements, Book II, Proposition 11; Book IV, Propositions 10–11; Book VI, Proposition 30; Book XIII, Propositions 1–6, 8–11, 16–18.

- ^ "῎Ακρον καὶ μέσον λόγον εὐθεῖα τετμῆσθαι λέγεται, ὅταν ᾖ ὡς ἡ ὅλη πρὸς τὸ μεῖζον τμῆμα, οὕτως τὸ μεῖζον πρὸς τὸ ἔλαττὸν."[18]

- ^ After Classical Greek sculptor Phidias (c. 490–430 BC);[33] Barr later wrote that he thought it unlikely that Phidias actually used the golden ratio.[34]

- ^ The theorem that non-square natural numbers have irrational square roots can be found in Euclid's Elements, Book X, Proposition 9.

Citations

- ^ a b c Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A001622 (Decimal expansion of golden ratio phi (or tau) = (1 + sqrt(5))/2)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- ^ Euclid. "Book 6, Definition 3". Elements.

- ^ Pacioli, Luca (1509). De divina proportione. Venice: Luca Paganinem de Paganinus de Brescia (Antonio Capella).

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 3, 81.

- ^

Summerson, John (1963). Heavenly Mansions and Other Essays on Architecture. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 37.

And the same applies in architecture, to the rectangles representing these and other ratios (e.g., the 'golden cut'). The sole value of these ratios is that they are intellectually fruitful and suggest the rhythms of modular design.

- ^ Herz-Fischler 1998.

- ^ Herz-Fischler 1998, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Strogatz, Steven (2012-09-24). "Me, Myself, and Math: Proportion Control". The New York Times.

- ^ Schielack, Vincent P. (1987). "The Fibonacci Sequence and the Golden Ratio". The Mathematics Teacher. 80 (5): 357–358. doi:10.5951/MT.80.5.0357. JSTOR 27965402. This source contains an elementary derivation of the golden ratio's value.

- ^ Peters, J. M. H. (1978). "An Approximate Relation between π and the Golden Ratio". The Mathematical Gazette. 62 (421): 197–198. doi:10.2307/3616690. JSTOR 3616690. S2CID 125919525.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 4: "... line division, which Euclid defined for ... purely geometrical purposes ..."

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Hemenway, Priya (2005). Divine Proportion: Phi In Art, Nature, and Science. New York: Sterling. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9781402735226.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Euclid (2007). Euclid's Elements of Geometry. Translated by Fitzpatrick, Richard. Lulu.com. p. 156. ISBN 978-0615179841.

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 88–96.

- ^ Mackinnon, Nick (1993). "The Portrait of Fra Luca Pacioli". The Mathematical Gazette. 77 (479): 130–219. doi:10.2307/3619717. JSTOR 3619717. S2CID 195006163.

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Baravalle, H. V. (1948). "The geometry of the pentagon and the golden section". Mathematics Teacher. 41: 22–31. doi:10.5951/MT.41.1.0022.

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 141.

- ^ Schreiber, Peter (1995). "A Supplement to J. Shallit's Paper 'Origins of the Analysis of the Euclidean Algorithm'". Historia Mathematica. 22 (4): 422–424. doi:10.1006/hmat.1995.1033.

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 151–152.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (2001). "The Golden Ratio". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ Fink, Karl (1903). A Brief History of Mathematics. Translated by Beman, Wooster Woodruff; Smith, David Eugene (2nd ed.). Chicago: Open Court. p. 223. (Originally published as Geschichte der Elementar-Mathematik.)

- ^ Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Petri, Bernhard (1996). "Fibonacci-Zahlen". Der Goldene Schnitt. Einblick in die Wissenschaft (in German). Vieweg+Teubner Verlag. pp. 87–98. doi:10.1007/978-3-322-85165-9_6. ISBN 978-3-8154-2511-4.

- ^ Herz-Fischler 1998, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Posamentier & Lehmann 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Posamentier & Lehmann 2011, p. 285.

- ^ Cook, Theodore Andrea (1914). The Curves of Life. London: Constable. p. 420.

- ^ Barr, Mark (1929). "Parameters of beauty". Architecture (NY). Vol. 60. p. 325. Reprinted: "Parameters of beauty". Think. Vol. 10–11. IBM. 1944.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (2001). "7. Penrose Tiles". The Colossal Book of Mathematics. Norton. pp. 73–93.

- ^

Livio 2002, pp. 203–209

Gratias, Denis; Quiquandon, Marianne (2019). "Discovery of quasicrystals: The early days". Comptes Rendus Physique. 20 (7–8): 803–816. Bibcode:2019CRPhy..20..803G. doi:10.1016/j.crhy.2019.05.009. S2CID 182005594.

Jaric, Marko V. (1989). Introduction to the Mathematics of Quasicrystals. Academic Press. p. x. ISBN 9780120406029.Although at the time of the discovery of quasicrystals the theory of quasiperiodic functions had been known for nearly sixty years, it was the mathematics of aperiodic Penrose tilings, mostly developed by Nicolaas de Bruijn, that provided the major influence on the new field.

Goldman, Alan I.; Anderegg, James W.; Besser, Matthew F.; Chang, Sheng-Liang; Delaney, Drew W.; Jenks, Cynthia J.; Kramer, Matthew J.; Lograsso, Thomas A.; Lynch, David W.; McCallum, R. William; Shield, Jeffrey E.; Sordelet, Daniel J.; Thiel, Patricia A. (1996). "Quasicrystalline materials". American Scientist. 84 (3): 230–241. JSTOR 29775669. - ^ Martin, George E. (1998). Geometric Constructions. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer. pp. 13–14. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0629-3. ISBN 978-1-4612-6845-1.

- ^ Hailperin, Max; Kaiser, Barbara K.; Knight, Karl W. (1999). Concrete Abstractions: An Introduction to Computer Science Using Scheme. Brooks/Cole. p. 63.

- ^ Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (1960) [1938]. "§11.8. The measure of the closest approximations to an arbitrary irrational". An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-19-853310-8.

- ^ Sizer, Walter S. (1986). "Continued roots". Mathematics Magazine. 59 (1): 23–27. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1986.11977215. JSTOR 2690013. MR 0828417.

- ^ Tattersall, James Joseph (1999). Elementary number theory in nine chapters. Cambridge University Press. p. 28.

- ^ Parker, Matt (2014). Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 284. ISBN 9780374275655.

- ^ a b c Burger, Edward B.; Starbird, Michael P. (2005) [2000]. The Heart of Mathematics: An Invitation to Effective Thinking (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 382. ISBN 9781931914413.

- ^ King, S.; Beck, F.; Lüttge, U. (2004). "On the mystery of the golden angle in phyllotaxis". Plant, Cell and Environment. 27 (6): 685–695. Bibcode:2004PCEnv..27..685K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01185.x.

- ^ Fletcher, Rachel (2006). "The golden section". Nexus Network Journal. 8 (1): 67–89. doi:10.1007/s00004-006-0004-z. S2CID 120991151.

- ^ a b c d e Loeb, Arthur (1992). "The Golden Triangle". Concepts & Images: Visual Mathematics. Birkhäuser. pp. 179–192. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0343-8_20. ISBN 978-1-4612-6716-4.

- ^ Miller, William (1996). "Pentagons and Golden Triangles". Mathematics in School. 25 (4): 2–4. JSTOR 30216571.

- ^ a b c d Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1987). Tilings and Patterns. New York: W. H. Freeman. pp. 537–547. ISBN 9780716711933.

- ^ Penrose, Roger (1978). "Pentaplexity". Eureka. Vol. 39. p. 32. (original PDF)

- ^

Frettlöh, D.; Harriss, E.; Gähler, F. "Robinson Triangle". Tilings Encyclopedia.

Clason, Robert G (1994). "A family of golden triangle tile patterns". The Mathematical Gazette. 78 (482): 130–148. doi:10.2307/3618569. JSTOR 3618569. S2CID 126206189.

- ^ Odom, George; van de Craats, Jan (1986). "E3007: The golden ratio from an equilateral triangle and its circumcircle". Problems and solutions. The American Mathematical Monthly. 93 (7): 572. doi:10.2307/2323047. JSTOR 2323047.

- ^ Busard, Hubert L. L. (1968). "L'algèbre au Moyen Âge : le "Liber mensurationum" d'Abû Bekr". Journal des Savants (in French and Latin). 1968 (2): 65–124. doi:10.3406/jds.1968.1175. See problem 51, reproduced on p. 98

- ^ Bruce, Ian (1994). "Another instance of the golden right triangle" (PDF). Fibonacci Quarterly. 32 (3): 232–233. doi:10.1080/00150517.1994.12429219.

- ^ Posamentier & Lehmann 2011, p. 11.

- ^ a b Grünbaum, Branko (1996). "A new rhombic hexecontahedron" (PDF). Geombinatorics. 6 (1): 15–18.

- ^ Senechal, Marjorie (2006). "Donald and the golden rhombohedra". In Davis, Chandler; Ellers, Erich W. (eds.). The Coxeter Legacy. American Mathematical Society. pp. 159–177. ISBN 0-8218-3722-2.

- ^ a b Loeb, Arthur L.; Varney, William (March 1992). "Does the golden spiral exist, and if not, where is its center?". In Hargittai, István; Pickover, Clifford A. (eds.). Spiral Symmetry. World Scientific. pp. 47–61. doi:10.1142/9789814343084_0002. ISBN 978-981-02-0615-4.

- ^ a b Reitebuch, Ulrich; Skrodzki, Martin; Polthier, Konrad (2021). "Approximating logarithmic spirals by quarter circles". In Swart, David; Farris, Frank; Torrence, Eve (eds.). Proceedings of Bridges 2021: Mathematics, Art, Music, Architecture, Culture. Phoenix, Arizona: Tessellations Publishing. pp. 95–102. ISBN 978-1-938664-39-7.

- ^ Diedrichs, Danilo R. (February 2019). "Archimedean, Logarithmic and Euler spirals – intriguing and ubiquitous patterns in nature". The Mathematical Gazette. 103 (556): 52–64. doi:10.1017/mag.2019.7. S2CID 127189159.

- ^ a b Livio (2002, pp. 70–72)

- ^ Gunn, Charles; Sullivan, John M. (2008). "The Borromean Rings: A video about the New IMU logo". In Sarhangi, Reza; Séquin, Carlo H. (eds.). Proceedings of Bridges 2008. Leeuwarden, the Netherlands. Tarquin Publications. pp. 63–70.; Video at "The Borromean Rings: A new logo for the IMU". International Mathematical Union. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08.

- ^ Hume, Alfred (1900). "Some propositions on the regular dodecahedron". The American Mathematical Monthly. 7 (12): 293–295. doi:10.2307/2969130. JSTOR 2969130.

- ^

Coxeter, H.S.M.; du Val, Patrick; Flather, H.T.; Petrie, J.F. (1938). The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra. Vol. 6. University of Toronto Studies. p. 4.

Just as a tetrahedron can be inscribed in a cube, so a cube can be inscribed in a dodecahedron. By reciprocation, this leads to an octahedron circumscribed about an icosahedron. In fact, each of the twelve vertices of the icosahedron divides an edge of the octahedron according to the "golden section.

- ^ Muller, J. M. (2006). Elementary functions : algorithms and implementation (2nd ed.). Boston: Birkhäuser. p. 93. ISBN 978-0817643720.

- ^ Yee, Alexander J. (2021-03-13). "Records Set by y-cruncher". numberword.org. Two independent computations done by Clifford Spielman.

- ^ Horocycles exinscrits : une propriété hyperbolique remarquable, cabri.net, retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ Berndt, Bruce C.; Chan, Heng Huat; Huang, Sen-Shan; Kang, Soon-Yi; Sohn, Jaebum; Son, Seung Hwan (1999). "The Rogers–Ramanujan Continued Fraction" (PDF). Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics. 105 (1–2): 9–24. doi:10.1016/S0377-0427(99)00033-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-10-06. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ Duffin, Richard J. (1978). "Algorithms for localizing roots of a polynomial and the Pisot Vijayaraghavan numbers". Pacific Journal of Mathematics. 74 (1): 47–56. doi:10.2140/pjm.1978.74.47.

- ^ Le Corbusier, The Modulor, p. 25, as cited in Padovan, Richard (1999). Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture. Taylor & Francis. p. 316. doi:10.4324/9780203477465. ISBN 9781135811112.

- ^ Frings, Marcus (2002). "The Golden Section in Architectural Theory". Nexus Network Journal. 4 (1): 9–32. doi:10.1007/s00004-001-0002-0. S2CID 123500957.

- ^ Le Corbusier, The Modulor, p. 35, as cited in

Padovan, Richard (1999). Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture. Taylor & Francis. p. 320. doi:10.4324/9780203477465. ISBN 9781135811112.

Both the paintings and the architectural designs make use of the golden section

- ^ Urwin, Simon (2003). Analysing Architecture (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b c d Livio, Mario (2002). "The golden ratio and aesthetics". Plus Magazine. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Devlin, Keith (2007). "The Myth That Will Not Go Away". Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

Part of the process of becoming a mathematics writer is, it appears, learning that you cannot refer to the golden ratio without following the first mention by a phrase that goes something like 'which the ancient Greeks and others believed to have divine and mystical properties.' Almost as compulsive is the urge to add a second factoid along the lines of 'Leonardo Da Vinci believed that the human form displays the golden ratio.' There is not a shred of evidence to back up either claim, and every reason to assume they are both false. Yet both claims, along with various others in a similar vein, live on.

- ^ Simanek, Donald E. "Fibonacci Flim-Flam". Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ Salvador Dalí (2008). The Dali Dimension: Decoding the Mind of a Genius (DVD). Media 3.14-TVC-FGSD-IRL-AVRO.

- ^ Hunt, Carla Herndon; Gilkey, Susan Nicodemus (1998). Teaching Mathematics in the Block. Eye On Education. pp. 44, 47. ISBN 1-883001-51-X.

- ^ Olariu, Agata (1999). "Golden Section and the Art of Painting". arXiv:physics/9908036.

- ^ Tosto, Pablo (1969). La composición áurea en las artes plásticas [The golden composition in the plastic arts] (in Spanish). Hachette. pp. 134–144.

- ^

Tschichold, Jan (1991). The Form of the Book. Hartley & Marks. p. 43 Fig 4. ISBN 0-88179-116-4.

Framework of ideal proportions in a medieval manuscript without multiple columns. Determined by Jan Tschichold 1953. Page proportion 2:3. margin proportions 1:1:2:3, Text area proportioned in the Golden Section. The lower outer corner of the text area is fixed by a diagonal as well.

- ^ Tschichold, Jan (1991). The Form of the Book. Hartley & Marks. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-88179-116-4.

- ^

Jones, Ronald (1971). "The golden section: A most remarkable measure". The Structurist. 11: 44–52.

Who would suspect, for example, that the switch plate for single light switches are standardized in terms of a Golden Rectangle?

Johnson, Art (1999). Famous problems and their mathematicians. Teacher Ideas Press. p. 45. ISBN 9781563084461.

The Golden Ratio is a standard feature of many modern designs, from postcards and credit cards to posters and light-switch plates.

Stakhov, Alexey P.; Olsen, Scott (2009). "§1.4.1 A Golden Rectangle with a Side Ratio of τ". The Mathematics of Harmony: From Euclid to Contemporary Mathematics and Computer Science. World Scientific. pp. 20–21.

A credit card has a form of the golden rectangle

Cox, Simon (2004). Cracking the Da Vinci Code. Barnes & Noble. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-84317-103-4.

The Golden Ratio also crops up in some very unlikely places: widescreen televisions, postcards, credit cards and photographs all commonly conform to its proportions.

- ^ Posamentier & Lehmann 2011, chapter 4, footnote 12: "The Togo flag was designed by the artist Paul Ahyi (1930–2010), who claims to have attempted to have the flag constructed in the shape of a golden rectangle".

- ^ Lendvai, Ernő (1971). Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music. London: Kahn and Averill.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 190.

- ^ Smith, Peter F. (2003). The Dynamics of Delight: Architecture and Aesthetics. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 9780415300100.

- ^ Howat, Roy (1983). "1. Proportional structure and the Golden Section". Debussy in Proportion: A Musical Analysis. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–10.

- ^ Trezise, Simon (1994). Debussy: La Mer. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780521446563.

- ^

Mongoven, Casey (2010). "A style of music characterized by Fibonacci and the golden ratio" (PDF). Congressus Numerantium. 201: 127–138.

Hasegawa, Robert (2011). "Gegenstrebige Harmonik in the Music of Hans Zender". Perspectives of New Music. 49 (1). Project Muse: 207–234. doi:10.1353/pnm.2011.0000. JSTOR 10.7757/persnewmusi.49.1.0207.

Smethurst, Reilly (2016). "Two Non-Octave Tunings by Heinz Bohlen: A Practical Proposal". In Torrence, Eve; et al. (eds.). Proceedings of Bridges 2016. Jyväskylä, Finland. Tessellations Publishing. pp. 519–522.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 154.

- ^

Padovan, Richard (1999). Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 305–306. doi:10.4324/9780203477465. ISBN 9781135811112.

Padovan, Richard (2002). "Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture". Nexus Network Journal. 4 (1): 113–122. doi:10.1007/s00004-001-0008-7.

- ^ Zeising, Adolf (1854). "Einleitung [preface]". Neue Lehre von den Proportionen des menschlichen Körpers [New doctrine of the proportions of the human body] (in German). Weigel. pp. 1–10.

- ^ Pommersheim, James E.; Marks, Tim K.; Flapan, Erica L., eds. (2010). Number Theory: A Lively Introduction with Proofs, Applications, and Stories. Wiley. p. 82.

- ^ Coldea, R.; Tennant, D.A.; Wheeler, E.M.; Wawrzynksa, E.; Prabhakaran, D.; Telling, M.; Habicht, K.; Smeibidl, P.; Keifer, K. (2010). "Quantum Criticality in an Ising Chain: Experimental Evidence for Emergent E8 Symmetry". Science. 327 (5962): 177–180. arXiv:1103.3694. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..177C. doi:10.1126/science.1180085. PMID 20056884. S2CID 206522808.

- ^ "A Disco Ball in Space". NASA. 2001-10-09. Archived from the original on 2020-12-22. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ^ Pheasant, Stephen (1986). Bodyspace. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780850663402.

- ^ van Laack, Walter (2001). A Better History Of Our World: Volume 1 The Universe. Aachen: van Laach.

- ^ Dunlap, Richard A. (1997). The Golden Ratio and Fibonacci Numbers. World Scientific. p. 130.

- ^ Falbo, Clement (March 2005). "The golden ratio—a contrary viewpoint". The College Mathematics Journal. 36 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1080/07468342.2005.11922119. S2CID 14816926.

- ^ Moscovich, Ivan (2004). The Hinged Square & Other Puzzles. New York: Sterling. p. 122. ISBN 9781402716669.

- ^ Peterson, Ivars (1 April 2005). "Sea shell spirals". Science News. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^

Man, John (2002). Gutenberg: How One Man Remade the World with Word. Wiley. pp. 166–167. ISBN 9780471218234.

The half-folio page (30.7 × 44.5 cm) was made up of two rectangles—the whole page and its text area—based on the so called 'golden section', which specifies a crucial relationship between short and long sides, and produces an irrational number, as pi is, but is a ratio of about 5:8.

- ^ Fechner, Gustav (1876). Vorschule der Ästhetik [Preschool of Aesthetics] (in German). Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. pp. 190–202.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 7.

- ^

Osler, Carol (2000). "Support for Resistance: Technical Analysis and Intraday Exchange Rates" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review. 6 (2): 53–68. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-05-12.

38.2 percent and 61.8 percent retracements of recent rises or declines are common,

- ^ Batchelor, Roy; Ramyar, Richard (2005). Magic numbers in the Dow (Report). Cass Business School. pp. 13, 31. Popular press summaries can be found in: Stevenson, Tom (2006-04-10). "Not since the 'big is beautiful' days have giants looked better". The Daily Telegraph. "Technical failure". The Economist. 2006-09-23.

- ^

Herz-Fischler, Roger (2000). The Shape of the Great Pyramid. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-324-5. The entire book surveys many alternative theories for this pyramid's shape. See Chapter 11, "Kepler triangle theory", pp. 80–91, for material specific to the Kepler triangle, and p. 166 for the conclusion that the Kepler triangle theory can be eliminated by the principle that "A theory must correspond to a level of mathematics consistent with what was known to the ancient Egyptians." See note 3, p. 229, for the history of Kepler's work with this triangle.

Rossi, Corinna (2004). Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–68.

there is no direct evidence in any ancient Egyptian written mathematical source of any arithmetic calculation or geometrical construction which could be classified as the Golden Section ... convergence to , and itself as a number, do not fit with the extant Middle Kingdom mathematical sources

; see also extensive discussion of multiple alternative theories for the shape of the pyramid and other Egyptian architecture, pp. 7–56Rossi, Corinna; Tout, Christopher A. (2002). "Were the Fibonacci series and the Golden Section known in ancient Egypt?". Historia Mathematica. 29 (2): 101–113. doi:10.1006/hmat.2001.2334. hdl:11311/997099.

Markowsky, George (1992). "Misconceptions about the Golden Ratio" (PDF). The College Mathematics Journal. 23 (1). Mathematical Association of America: 2–19. doi:10.2307/2686193. JSTOR 2686193. Retrieved 2012-06-29.

It does not appear that the Egyptians even knew of the existence of much less incorporated it in their buildings

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Van Mersbergen, Audrey M. (1998). "Rhetorical Prototypes in Architecture: Measuring the Acropolis with a Philosophical Polemic". Communication Quarterly. 46 (2): 194–213. doi:10.1080/01463379809370095.

- ^ Devlin, Keith J. (2005). The Math Instinct. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 108.

- ^ Gazalé, Midhat J. (1999). Gnomon: From Pharaohs to Fractals. Princeton. p. 125. ISBN 9780691005140.

- ^ Foutakis, Patrice (2014). "Did the Greeks Build According to the Golden Ratio?". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 24 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1017/S0959774314000201. S2CID 162767334.

- ^ Le Salon de la Section d'Or, October 1912, Mediation Centre Pompidou

- ^ Jeunes Peintres ne vous frappez pas !, La Section d'Or: Numéro spécial consacré à l'Exposition de la "Section d'Or", première année, no. 1, 9 octobre 1912, pp. 1–7 Archived 2020-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, Bibliothèque Kandinsky

- ^ Herz-Fischler, Roger (1983). "An Examination of Claims Concerning Seurat and the Golden Number" (PDF). Gazette des Beaux-Arts. 101: 109–112.

- ^ Herbert, Robert (1968). Neo-Impressionism. Guggenheim Foundation. p. 24.

- ^ Livio 2002, p. 169.

- ^ a b Camfield, William A. (March 1965). "Juan Gris and the golden section". The Art Bulletin. 47 (1): 128–134. doi:10.1080/00043079.1965.10788819.

- ^

Green, Christopher (1992). Juan Gris. Yale. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9780300053746.

Cottington, David (2004). Cubism and Its Histories. Manchester University Press. pp. 112, 142.

- ^ Allard, Roger (June 1911). "Sur quelques peintres". Les Marches du Sud-Ouest: 57–64. Reprinted in Antliff, Mark; Leighten, Patricia, eds. (2008). A Cubism Reader, Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 178–191.

- ^ Bouleau, Charles (1963). The Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in Art. Harcourt, Brace & World. pp. 247–248.

- ^ Livio 2002, pp. 177–178.

Works cited

- Herz-Fischler, Roger (1998) [1987]. A Mathematical History of the Golden Number. Dover. ISBN 9780486400075. (Originally titled A Mathematical History of Division in Extreme and Mean Ratio.)

- Livio, Mario (2002). The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 9780767908153.

- Posamentier, Alfred S.; Lehmann, Ingmar (2011). The Glorious Golden Ratio. Prometheus Books. ISBN 9-781-61614-424-1.

Further reading

- Doczi, György (1981). The Power of Limits: Proportional Harmonies in Nature, Art, and Architecture. Boston: Shambhala.

- Hargittai, István, ed. (1992). Fivefold Symmetry. World Scientific. ISBN 9789810206000.

- Huntley, H. E. (1970). The Divine Proportion: A Study in Mathematical Beauty. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-22254-7.

- Schaaf, William L., ed. (1967). The Golden Measure (PDF). California School Mathematics Study Group Reprint Series. Stanford University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-25.

- Scimone, Aldo (1997). La Sezione Aurea. Storia culturale di un leitmotiv della Matematica. Palermo: Sigma Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-7231-025-0.

- Walser, Hans (2001) [Der Goldene Schnitt 1993]. The Golden Section. Peter Hilton trans. Washington, DC: The Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-534-8.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Golden Ratio". MathWorld.

- Bogomolny, Alexander (2018). "Golden Ratio in Geometry". Cut-the-Knot.

- Knott, Ron. "The Golden section ratio: Phi". Information and activities by a mathematics professor.

- The Myth That Will Not Go Away Archived 2020-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, by Keith Devlin, addressing multiple allegations about the use of the golden ratio in culture.

- Spurious golden spirals collected by Randall Munroe

- YouTube lecture on Zeno's mice problem and logarithmic spirals

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\varphi ^{2}&=\varphi +1=2.618033\dots ,\\[5mu]{\frac {1}{\varphi }}&=\varphi -1=0.618033\dots .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ff2e5225abf67548cf93c882add3a4b439c4aeb8)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\varphi ^{n}&=\varphi ^{n-1}+\varphi ^{n-3}+\cdots +\varphi ^{n-1-2m}+\varphi ^{n-2-2m}\\[5mu]\varphi ^{n}-\varphi ^{n-1}&=\varphi ^{n-2}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/048f09b7012c7fbd3d9f32798de6dd5c01acabcd)

![{\displaystyle \varphi =[1;1,1,1,\dots ]=1+{\cfrac {1}{1+{\cfrac {1}{1+{\cfrac {1}{1+{{\vphantom {1}} \atop \ddots }}}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b68e302b5301938b37b40e527a07c83a1f58e830)

![{\displaystyle \varphi ^{-1}=[0;1,1,1,\dots ]=0+{\cfrac {1}{1+{\cfrac {1}{1+{\cfrac {1}{1+{{\vphantom {1}} \atop \ddots }}}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/224ea872a3a53d5fbe1ab6d1a9a67c37e5320bed)

![{\displaystyle F\left(n\right)={\frac {\varphi ^{n}-(-\varphi )^{-n}}{\sqrt {5}}}={\frac {\varphi ^{n}-(1-\varphi )^{n}}{\sqrt {5}}}={\frac {1}{\sqrt {5}}}\left[\left({1+{\sqrt {5}} \over 2}\right)^{n}-\left({1-{\sqrt {5}} \over 2}\right)^{n}\right],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/39f21f2e88f64b0eaad9edea3312e5dea6446713)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&{\bigl \vert }L_{n}-{\sqrt {5}}F_{n}{\bigr \vert }={\frac {2}{\varphi ^{n}}}\to 0,\\[5mu]&{\bigl (}{\tfrac {1}{2}}L_{3n}{\bigr )}^{2}=5{\bigl (}{\tfrac {1}{2}}F_{3n}{\bigr )}^{2}+(-1)^{n}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b76ec76fed5b0692ae8e9be070b4c2d620aa69ef)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}3\varphi ^{3}-5\varphi ^{2}+4&=3(\varphi ^{2}+\varphi )-5\varphi ^{2}+4\\[5mu]&=3{\bigl (}(\varphi +1)+\varphi {\bigr )}-5(\varphi +1)+4\\[5mu]&=\varphi +2\approx 3.618033.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9eba46117303993ef0998e4dc1c99ef34e511a00)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\varphi ^{0}&=1,\\[5mu]\varphi ^{1}&=1.618033989\ldots \approx 2,\\[5mu]\varphi ^{2}&=2.618033989\ldots \approx 3,\\[5mu]\varphi ^{3}&=4.236067978\ldots \approx 4,\\[5mu]\varphi ^{4}&=6.854101967\ldots \approx 7,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c4ac9ddf7e52ee6d1d0976b18e49ea4a99375dee)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {2\pi -g}{g}}&={\frac {2\pi }{2\pi -g}}=\varphi ,\\[8mu]2\pi -g&={\frac {2\pi }{\varphi }}\approx 222.5^{\circ }\!,\\[8mu]g&={\frac {2\pi }{\varphi ^{2}}}\approx 137.5^{\circ }\!.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/40b2a5dd8ad7ae0f2e1c53bb43bb82e62d85e348)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\varphi &=1+2\sin(\pi /10)=1+2\sin 18^{\circ }\!,\\[5mu]\varphi &={\tfrac {1}{2}}\csc(\pi /10)={\tfrac {1}{2}}\csc 18^{\circ }\!,\\[5mu]\varphi &=2\cos(\pi /5)=2\cos 36^{\circ }\!,\\[5mu]\varphi &=2\sin(3\pi /10)=2\sin 54^{\circ }\!.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7a0a8da53781e6f8e49ac9f4d5b9331a3ddf4dbf)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A&={\tfrac {1}{2}}s^{2}{\sqrt {\varphi {\vphantom {+}}}},\\[5mu]\theta &=\sin ^{-1}{\frac {1}{\varphi }}\approx 38.1727^{\circ }\!,\\[5mu]\theta &=\cos ^{-1}{\frac {1}{\varphi }}\approx 51.8273^{\circ }\!.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/779f1f91238ee7d20831ce7a01708467f451686d)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\alpha &=2\arctan {1 \over \varphi }\approx 63.43495^{\circ }\!,\\[5mu]\beta &=2\arctan \varphi =\pi -\arctan 2=\arctan 1+\arctan 3\approx 116.56505^{\circ }\!.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c119812addb94dc1e424cadd77557bd18fd278ce)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}d&={\frac {2a}{\sqrt {2+\varphi }}}=2{\sqrt {\frac {3-\varphi }{5}}}a\approx 1.05146a,\\[5mu]D&=2{\sqrt {\frac {2+\varphi }{5}}}a\approx 1.70130a.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1e065f9b4f3ea5c64f0201b0a37108b249b2b7e0)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A&=\sin(\arctan 2)\cdot a^{2}={2 \over {\sqrt {5}}}~a^{2}\approx 0.89443a^{2},\\[5mu]A&={{\varphi } \over 2}d^{2}\approx 0.80902d^{2}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/046e7158ac6208efb25197529492b0151b305d72)

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {Z} [\varphi ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/14f984c2710477c64fca0f16a71928134bdb8201)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}e^{0}+e^{-0}&=2,\\[5mu]e^{2\pi i/5}+e^{-2\pi i/5}&=\varphi ^{-1}=-1+\varphi ,\\[5mu]e^{4\pi i/5}+e^{-4\pi i/5}&=-\varphi .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bec7bcbd2e99aef0874eb163966c3e2dd9424b86)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}e^{\pi i}+e^{-\pi i}&=-2,\\[5mu]e^{\pi i/5}+e^{-\pi i/5}&=\varphi ,\\[5mu]e^{3\pi i/5}+e^{-3\pi i/5}&=-\varphi ^{-1}=1-\varphi .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9459634b32b6990a97eb560ce696a3bc2e722513)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\Bigl (}\varphi +R{{\bigl (}e^{-2a}{\bigr )}}{\Bigr )}{\Bigl (}\varphi +R{{\bigl (}e^{-2b}{\bigr )}}{\Bigr )}&=\varphi {\sqrt {5}},\\[5mu]{\Bigl (}\varphi ^{-1}-R{{\bigl (}{-e^{-a}}{\bigr )}}{\Bigr )}{\Bigl (}\varphi ^{-1}-R{{\bigl (}{-e^{-b}}{\bigr )}}{\Bigr )}&=\varphi ^{-1}{\sqrt {5}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/efa72855991c37845330a894d36b1d91647a265a)